- Product

Item Misfit: Listening to What the Work Is Telling You

👉 How to use: Select your use case above to generate a prompt that references the full RM Compare Product Portal. Copy and paste into ChatGPT/Claude to turn "Misfit" data into action.

If judge misfit shows where people see things differently, item misfit shows where the work itself is provoking disagreement. In an RM Compare report, item misfit does not mean “bad work” or “faulty items.” It means, very specifically, “here are the pieces of work that your judging pool did not see in the same way.” Those items are often where your assessment task, your construct, and your judges’ thinking come most sharply into focus.

What Item Misfit Actually Is

Item misfit is the item‑level version of the same idea used for judge misfit: it measures how far an item’s observed win–loss pattern deviates from what the Rasch model predicts, given its estimated position on the quality scale. In a well‑behaved session, an item estimated as “strong” should tend to win against weaker items and sometimes lose against very strong ones; deviations from that pattern are expected in close calls but should balance out over many comparisons.

The misfit index aggregates these deviations (residuals) across all comparisons involving that item:

- Items whose decisions broadly follow the model (winning when expected, losing when expected, with only small surprises) have low misfit.

- Items that repeatedly “behave strangely” - losing when they should win or winning when they should lose, according to the model - accumulate higher misfit.

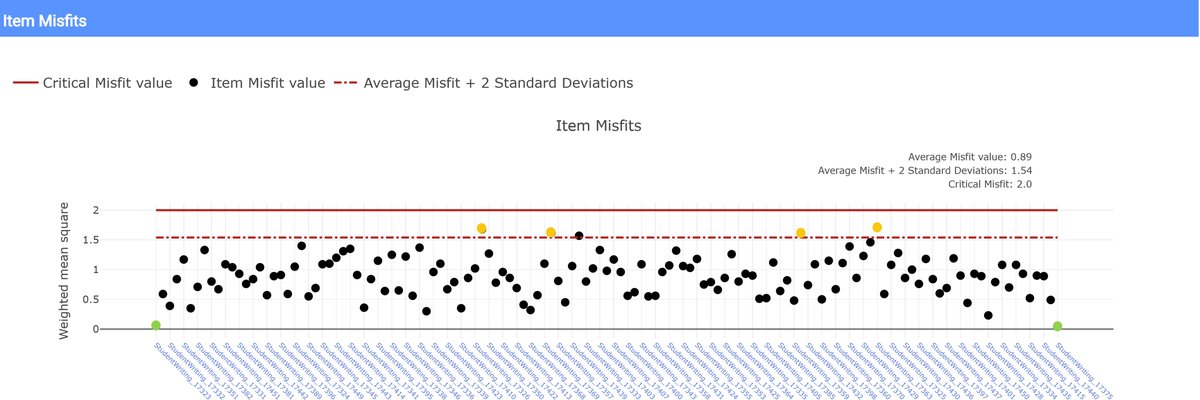

In RM Compare, items that fall more than about two standard deviations above the mean misfit score are flagged as “non‑consensual items,” typically shown above a dashed line, with a higher “critical misfit” line indicating very strong evidence of unusual behaviour. To put it simply: item misfit “shows non‑consensual Items. These are Items that the judging pool did not share the same perception of value.”

How to Read the Item Misfit Graph

The item misfit report is visually similar to the judge misfit graph: each dot is a piece of work, plotted by misfit level, with red lines marking thresholds. Some implementations colour or label interesting items (for example, those above the dashed line, or particular cases highlighted in the narrative).

A practical reading routine:

Scan the pattern of dots.

- If almost all items sit well below the dashed line, your judges reached a strong consensus about the relative value of most work; any misfit items are exceptions to a generally shared story.

- If many items are near or above the line, that suggests the cohort’s work, the task, or the construct is provoking widespread disagreement about value

Locate the misfitting items in the rank order.

- Misfit can occur at any point on the scale: a top‑ranked item might be controversial because some judges see it as brilliant while others see it as flawed; a mid‑range item might sit on a conceptual boundary; a low‑ranked item might split opinion about minimum acceptability.

- Move from the misfit graph into the rank order to see where each flagged item sits; that positional context will shape how you interpret it.

Look at each misfitting item as an artefact, not just a dot.

- Open the item and, if possible, review a sample of the comparisons in which it was involved (especially where judges disagreed with the predicted outcome). This is where the abstract statistic turns back into concrete professional judgement.

Treat the misfit graph as a signpost; the real insight comes when you inspect the underlying work and judgements.

Why Items Misfit – And Why That Matters

Research on Rasch item fit highlight several common reasons for item misfit, many of which are productive rather than problematic.

Typical causes include:

- Boundary or threshold items.

Some pieces of work sit right on a decision boundary: for example, just between “secure” and “exceeding” the standard. Different judges, all acting reasonably, may legitimately disagree on which side of the line they fall, creating a pattern of wins and losses that looks erratic from the model’s perspective. - Multidimensional or ambiguous tasks.

If an item taps more than one construct (e.g. creativity and technical accuracy) and your holistic statement is not crystal clear about which to prioritise, judges may implicitly weight these dimensions differently, leading to inconsistent comparisons for that item. - Unusual or innovative responses.

An item might be genuinely original, taking an approach that some judges reward highly and others penalise because it falls outside their expectations. These items often trigger high misfit because they do not behave like the “typical” work on the same part of the scale. - Task problems.

Occasionally, misfit items expose flaws in task wording, resource access, or guidance: perhaps a question invited multiple interpretations, or a particular format disadvantaged some students in a way not anticipated.

From a validity perspective, misfit is a red flag that the simple “one‑dimension” story is under pressure: either the item is measuring something slightly different, or judges are bringing different latent constructs to bear. That is not automatically a reason to remove the item; it is a reason to investigate what the item is really showing you.

Using Item Misfit to Improve Tasks and Teaching

Handled well, item misfit becomes one of the richest sources of information for improving both assessments and instruction.

Practical ways to use it:

- Refine tasks and materials.

If several misfitting items share a design feature (for example, ambiguous phrasing, unfamiliar context, or awkward formatting), that is strong evidence to revise the task before using it again. You might clarify language, provide more structured prompts, or adjust stimulus materials. - Clarify your construct.

If boundary or multidimensional items keep misfitting, it may be because your holistic statement or shared understanding of “what good looks like” is not precise enough. Use misfitting items as the centrepiece of moderation conversations: “What exactly is strong here? What are we willing to trade off?” - Build exemplar collections.

Misfitting items at the top, middle, and bottom of the scale often make powerful exemplars for professional learning or for student feedback, precisely because they are contentious. Annotating them and capturing the different readings can help future judges (and learners) navigate the grey areas around standards. - Spot unexpected strengths or weaknesses.

Sometimes misfit reveals that your students can do something you did not explicitly design for (e.g. creative risk‑taking) or that a particular skill (e.g. argument structure) is more variable than you thought. That can inform both curriculum planning and future assessment design.

The key shift is from seeing misfit as “noise to be stripped out” to “signal about where our current model of the construct is under strain.”

When (and Whether) to “Fix” Misfitting Items

Technical literature on Rasch and item response theory shows that removing misfitting items can sometimes improve the statistical properties of a scale, but that doing so without considering practical significance can distort what you are actually measuring. In RM Compare contexts, your response should depend on stakes and purpose:

- Low- to medium‑stakes use (classroom, internal moderation, peer assessment).

It will usually be more valuable to keep misfitting items in the analysis, note their presence, and use them as prompts for professional dialogue and task refinement. You can mention in any write‑up that certain items showed low consensus and explain how you responded. - High‑stakes or formal standard‑setting use.

Here, you might run sensitivity checks: compare the rank order and key decisions (such as cut‑points) with and without the most extreme misfitting items. If your conclusions are robust, you can keep the items; if they are fragile, you may decide to remove or redesign those items in future cycles and document the rationale.

In both cases, the important thing is transparency: misfit should lead to questions, investigation, and, where necessary, design changes, not to quiet deletion without reflection.

Item Misfit and Overall Session Health

Within the “session health” framework:

- A healthy session will typically show a small number of misfitting items that you can understand once you examine them - boundary cases, innovative responses, or task quirks you can now articulate.

- An unhealthy session may show many misfitting items, or misfit concentrated in areas that align with known weaknesses in task design or briefing (for example, all items using a particular unfamiliar genre or data set).

Reading item misfit alongside judge misfit and the rank order helps you distinguish between:

- A construct that is genuinely complex and contested (many interesting misfitting items, but judges otherwise aligned), and

- A process problem where both judges and items are pulling in different directions because the task or construct was not clearly specified.

In the final post of this series, the focus will turn to designing healthy sessions from the start. We will use what you now know about rank order, judge misfit and item misfit to make better decisions about task design, judge briefing, number of items and judgements, and real‑time monitoring so that low reliability and confusing misfit feel less like nasty surprises and more like manageable, anticipated risks.