- Product

Judge Misfit: Making Sense of Agreement and Difference

👉 How to use: Select your use case above. The generated prompt will instruct the AI to create a strategy that links back to this guide for your team to follow.

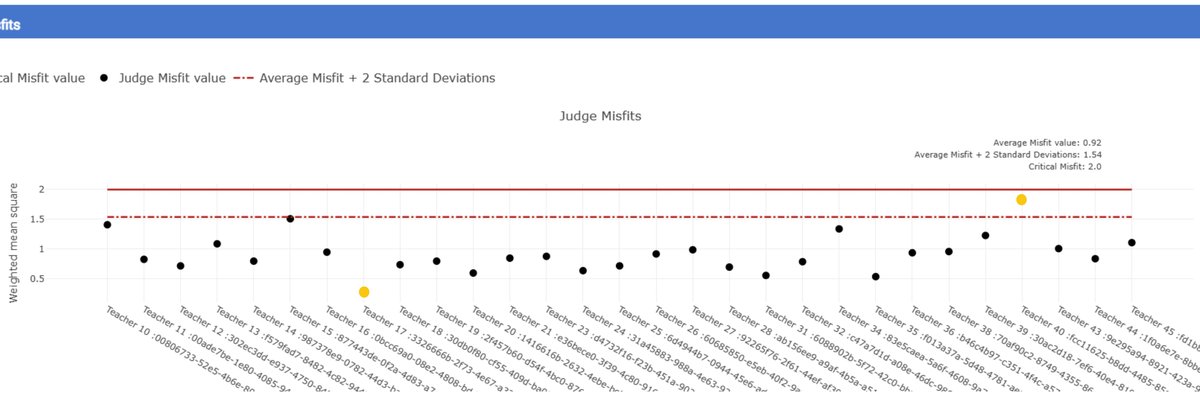

When users first encounter the judge misfit graph in an RM Compare report, the immediate worry is often: “Have my judges done it wrong?” The term “misfit,” red threshold lines, and dots floating above them can feel like an accusation. This post reframes judge misfit as a structured way of seeing where judges are not sharing the same view of value as everyone else, and therefore where the richest professional conversations and the most important quality checks can happen.

What Judge Misfit Actually Measures

Judge misfit describes how far a judge’s pattern of decisions deviates from what the Rasch model would expect, given the emerging consensus in the session. In a well-functioning comparative judgement process, judges will disagree sometimes, but across many comparisons their decisions will broadly line up with a single underlying scale of quality: stronger items should tend to win against weaker ones, especially when differences are large.

The misfit statistic aggregates how surprising a judge’s decisions are when compared to that model:

- If a judge frequently chooses an item that the model (based on all other judges’ behaviour) predicts should lose, their residuals - the differences between expected and observed decisions - accumulate.

- These residuals are combined into a standard misfit index.

- In RM Compare reports, judges whose misfit is more than two standard deviations above the mean are flagged (shown above the dashed red line), with a “critical misfit” threshold shown by a solid red line for particularly extreme cases.

A judge above the dashed line is not automatically “bad”; it simply means their pattern of decisions is systematically different enough from the group to warrant attention.

How to Read the Judge Misfit Graph

The judge misfit view in the standard report plots each judge as a point on a the horizontal axis with the red lines marking key thresholds. Alongside misfit, you have access to context metrics in other parts of the reporting such as number of judgements per judge and average time to decision.

A simple three-step reading:

Glance at the overall distribution.

- Are most judges clustered comfortably under the dashed line, with perhaps one or two outliers? That suggests a broadly shared construct with a small number of non‑consensual judges.

- Are many judges close to or above the line? That is a hint that your construct or briefing may not have been shared clearly, or that the judging pool is highly heterogeneous in how they interpret quality.

Note how far outliers are.

- Judges just above the dashed line may simply be using a slightly different emphasis or having difficulty with a subset of items.

- Judges above the solid “critical misfit” line are behaving in a way that is strongly at odds with the emerging model and almost always deserve a closer look.

Bring in context: workload and timing.

- Judges who have made very few judgements can show unstable misfit values simply because the model has little evidence about them; treat very small workloads with caution.

- Decision time data show whether a judge is consistently much faster or slower than their peers. Extremely fast decisions can be a red flag for superficial judging, and extremely slow ones can signal uncertainty. However RM Compare’s own analysis shows that faster judges are not automatically more prone to misfit, so time data should be read alongside misfit, not instead of it.

The key is to see the misfit graph as a map of how aligned your judging team was, not a scoreboard of competence.

Why Judge Misfit Does Not Always Mean “Wrong”

There are at least three common, and quite different, reasons a judge might be flagged:

- Different but coherent construct.

A judge may apply a different (but internally consistent) standard, perhaps valuing creativity over technical accuracy, or originality over polish. Their decisions look like misfit because they systematically prefer a different type of quality than the rest of the team, not because they are random or careless. - Genuine misunderstanding or drift.

A judge might have misunderstood the holistic statement, misinterpreted the task, or gradually drifted in their interpretation of what “good” looks like during the session. In traditional marking, this often goes unnoticed; in ACJ, misfit flags give you early warning so you can intervene or at least interpret results with caution. - Noise: too little data or tricky comparisons.

If a judge only made a small number of judgements, or happened to see a disproportionate number of very close pairs, their misfit can be artificially inflated. That is why workload and the nature of the items judged matter when you interpret the statistic.

In all cases, misfit is best treated as a question rather than an answer: “What is going on with this judge’s decisions, and what does that tell us about our construct, our task, and our process?”

Using Judge Misfit to Support, Not Punish, Judges

Handled well, judge misfit data become a tool for calibration and professional learning rather than a mechanism for blame.

Practical steps you can take:

- Start with conversation, not exclusion.

For any judge above the dashed line, begin by reviewing a sample of their comparisons and asking them to talk through their reasoning. Are they seeing something important that the rest of the group is missing? Or are they unclear about the construct? - Look for patterns, not one‑offs.

Is the judge consistently favouring a particular type of response (e.g. highly creative but technically flawed work)? If so, this may highlight a disagreement within the team about what the construct should prioritise, which can then be discussed and, if necessary, resolved. - Use misfit to refine your briefing.

If several judges are misfitting in similar ways, that is often feedback on the clarity of your holistic statement, guidance materials, or pre‑session exemplars. Updating these before the next session is more productive than simply removing or discounting judges. - Consider technical interventions only when necessary.

In high‑stakes contexts, where misfit is both large and clearly due to misunderstanding or erratic behaviour, you may decide to discount a judge’s contribution or rerun part of the session. If you do this, document the reasoning carefully and, where possible, use the experience to improve judge training rather than treating it as a one‑off fix.

This approach preserves the integrity of the process. Regulators and researchers explicitly note that misfit analysis is a key part of demonstrating that a comparative judgement system is functioning responsibly.

Judge Misfit as a Live Quality-Control Tool

One advantage of RM Compare is that misfit can be monitored while a session is still running, not just afterwards. This turns judge misfit into a live quality-control mechanism:

- Early detection. If a judge is quickly emerging as a clear outlier, you can check in with them, clarify expectations, or adjust allocations before too many comparisons are affected.

- Targeted support. If a judge is taking much longer than others and showing high misfit, they may need more support or a smaller judging load; this is especially common in early uses of ACJ where the process itself is unfamiliar.

- Ongoing calibration. You can use early misfit patterns to prompt short calibration discussions mid‑session (for example, sharing anonymised pairs that different judges ranked differently and discussing why).

Thinking this way, judge misfit becomes your friend: it is the part of the system that keeps asking “Are we really judging the same thing in the same way?” rather than letting hidden differences go unchallenged.

How Judge Misfit Connects to Session Health

In terms of the “session health” idea from earlier posts, judge misfit is your main indicator of alignment:

- A healthy session typically shows most judges comfortably below the misfit thresholds, with perhaps one or two outliers whose decisions you understand after investigation.

- An unhealthy session might show several judges with high misfit, especially if their reasoning reveals fundamentally different interpretations of the construct or clear misunderstandings of the task.

When you read judge misfit alongside the rank order and reliability, you can distinguish between:

- A session where reliability is moderate because judges are grappling honestly with a difficult construct but are broadly aligned, and

- A session where reliability is undermined by serious conceptual divergence within the judging team.

In the next post, the focus will pivot to item misfit: how to read it, why “difficult” items are often the most enlightening, and how to use item misfit to improve task design and deepen collective understanding of what good work looks like.