- Product

Reading the Rank Order: What Story Is Your Session Telling?

👉 How to use: Select your use case above. The generated prompt will instruct the AI to analyze your results using the principles from the RM Compare "Reading the Rank Order" guide.

The rank order is the heart of an RM Compare report: it is the clearest expression of what your judges, working together, thought about the relative quality of the work. Understanding how to read it (beyond “who came first and last”) is the fastest way to move from staring at a graph to making confident decisions about your session’s health.

What the Rank Order Actually Shows

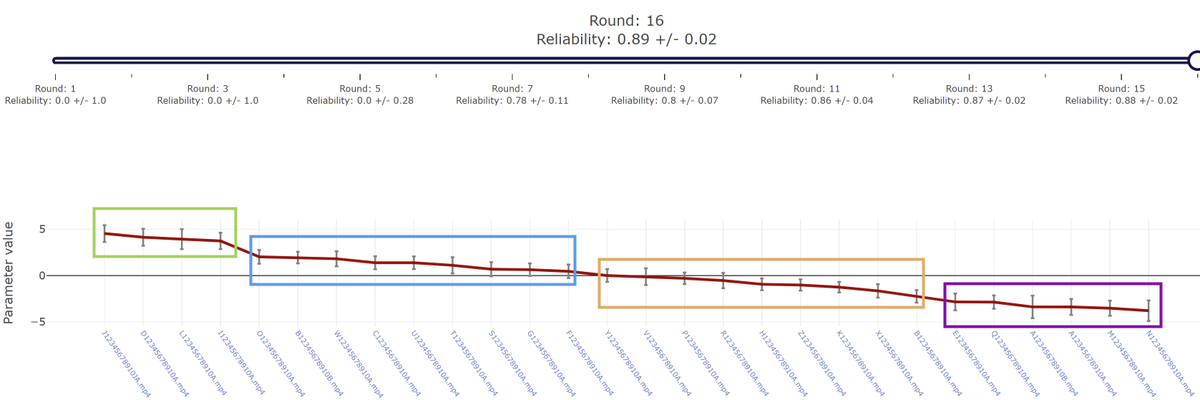

The rank order view lists all items from “strongest” to “weakest” on a single underlying scale of quality estimated from the pairwise judgements. Instead of marks or levels, each item gets a parameter value (often somewhere between about +5 and −5), which represents its position on this scale: higher values mean the item was more often preferred against a wide range of competitors; lower values mean it was more often judged weaker.

Two key features to look at:

- The spread of parameter values. A wide spread (e.g. top items at +4 or +5, bottom items at −4 or −5) suggests that judges perceived clear differences in quality; a tight spread means the work is more similar and harder to separate.

- The shape of the line. Where the graph connects items in order, steep drops indicate big jumps in perceived quality, while long shallow sections indicate clusters of very similar work.

A good first question to ask is: If I click into a few items at different points on this scale, does the pattern “feel” right for this cohort and this task? That qualitative sense-check is an essential part of judging session health.

How Rank Order and Reliability Work Together

On the same report, you’ll see a reliability statistic (Scale Separation Reliability) that summarises how consistently the model can distinguish between items on this scale. In comparative judgement studies, values around 0.7 can be useful for lower‑stakes or exploratory work, 0.8+ is generally regarded as good, and 0.9+ is often achieved in well‑run sessions and compares favourably with traditional marking reliability.

Three practical principles:

- Use reliability to judge confidence in gaps, not just in order. A session with reliability in the high 0.8s is telling you that the distances between items on the scale are fairly stable as well as their relative order. This matters when you want to make finer distinctions (e.g. grade boundaries or detailed rank‑based decisions).

- Match expectations to purpose. For formative classroom use or internal moderation, a rank order with reliability around 0.7–0.8 can still give powerful insight, especially if you focus on broad groupings (top, middle, bottom) and use the work as the basis for conversation. For high‑stakes standard setting, you would normally aim higher and design the session accordingly (more items, more judgements per item, appropriately briefed judges).

- Look at reliability and the shape of the rank. A theoretically “good” reliability is less reassuring if the top few items look oddly weak on inspection, or if several items are bunched together where you need sharp distinctions. Conversely, a moderate reliability with a very clear visual spread and coherent story may be perfectly acceptable for some purposes.

The message: reliability helps you understand how much faith to put in the precision of the rank order, but your professional reading of the work should remain central.

Using the Rank to Assess Session Health

Once you are comfortable with the basics, you can start to read the rank order as a quick “health check” on your session.

Look for:

- Coherent extremes. Do the highest‑ranked and lowest‑ranked items clearly look like the strongest and weakest examples for this task? If not, that can point to issues in the construct, the task, or the judging instructions.

- Meaningful clusters. Are there natural bands of items where quality looks similar (e.g. a group of mid‑range responses that all meet the standard but don’t exceed it)? These clusters are often more practically useful than the precise fine‑grained order within them.

- Unexpected outliers. Are there items whose position surprises you even after you inspect them? These can be early flags for further investigation via item misfit (is this a genuinely boundary‑pushing piece of work?) or judge misfit (were particular judges seeing this differently?).

You can also compare the rank order with other information you have:

- With prior expectations. If all your high‑attaining students are unexpectedly low in the rank, that might say something important about how the task tapped (or failed to tap) the construct you care about.

- With other assessments. Over time, you can look at how items or students ranked via RM Compare line up with their performance on other measures, helping you build a picture of convergent evidence rather than relying on any single instrument.

Used this way, the rank order stops being “just a list” and becomes a structured story you can query.

What to Do When the Rank Order or Reliability Worries You

In practice, there are three common worry‑states:

- Reliability is lower than hoped, but the rank order “looks about right.”

In this case, consider whether your use‑case really demands higher reliability. For many formative or developmental uses, an approximately right order backed by actual inspection of work may be acceptable. You can still document limitations (e.g. small judge team, small item pool) and use the experience to strengthen design next time. - Reliability is reasonable, but parts of the rank order feel wrong.

Here, dig down into those surprising items. Look at who judged them, how often, and whether they appear as misfitting items or are frequently involved in comparisons from misfitting judges. Sometimes the “wrongness” reflects a hidden assumption in your own mental model; sometimes it surfaces genuine problems in task design or briefing. - Both reliability and face validity of the rank are poor.

This typically points to deeper design issues: too few judgements per item, judges with very different interpretations of the construct, or tasks that elicit highly heterogeneous responses that don’t map cleanly onto a single dimension. In these cases, the most productive response is not to squeeze more meaning out of the existing report, but to treat it as feedback for redesign, something that will be taken up explicitly in the later “designing healthy sessions” post.

In every case, the question is the same: Given what this rank order and reliability are telling me, is the session healthy enough for the decision or learning purpose I have in mind—and if not, what will I change next time? The next posts will add judge misfit and item misfit to that picture, giving you more tools to diagnose why the rank looks the way it does and how to improve session health systematically.