- Opinion

The Myth of the "Perfect Photo": Why Mobile Capture can be Fairer, Faster, and Just as Reliable

Key Points

- Teachers and students often over‑invest in “perfect” scans and studio‑quality photos because they assume image quality directly determines assessment quality, creating unnecessary workload and stress.

- Cognitive science concepts like Perceptual Constancy show that human judges mentally correct for lighting, angle and minor blur, allowing them to focus on the underlying work as long as it is broadly legible.

- Demanding high‑end, polished imagery introduces “production value bias”, advantaging students with better cameras, software and support, whereas quick, in‑class mobile capture can be fairer by stripping away presentation advantages.

- Evidence from RM Compare’s work with E‑ACT on 3D clay sculptures shows that simple mobile photos can still deliver very high reliability because expert judges use tacit knowledge to infer texture, depth and quality from imperfect images.

👉 How to use: Select your use case above. The generated prompt will instruct the AI to design a "Mobile Capture" strategy based on the science of Perceptual Constancy described in the blog.

Introduction

If you have ever run an assessment session for Art, Design, or Engineering, you know the "Scanner Dread."

It’s that sinking feeling that before you can judge student work, you must first become a professional photographer. Teachers spend hours after school standing over slow flatbed scanners. Students stress over setting up "studio lighting" in their bedrooms. We obsess over camera angles, white balance, and crop margins.

Why do we do this? Because we are driven by a deep-seated fear: "If the photo is bad, the grade will be bad."

We assume that a blurry photo hides the quality of the work. We assume that if a drawing is photographed under yellow classroom lights, the examiner will think the drawing itself is yellow. We assume that Image Quality = Assessment Quality.

But science suggests we are worrying about the wrong thing.

In Part 1 of this series, we talked about Amodal Completion—your brain's ability to see "the whole cat" behind a fence. Today, we need to talk about its partner: Perceptual Constancy. It is the reason why you don't need a professional studio to get reliable assessment results. You just need a smartphone and a human brain.

The Science: Signal vs. Noise

To an Artificial Intelligence, a photo is just a grid of pixels.

- If you take a photo of a white page in a dark room, the AI reads the pixel value as "Grey."

- If you take a photo of a circular plate from a side angle, the AI reads the shape as "Oval."

- AI sees the data.

Humans, however, see the object.

Perceptual Constancy is your brain's built-in normalisation software. It constantly adjusts for environmental "Noise" (lighting, distance, angle) to preserve the "Signal" (the true object).

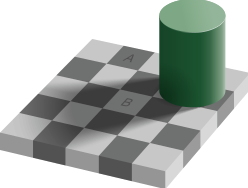

To prove it, look at the famous Adelson's Checker-Shadow Illusion.

The Illusion: Look at square A and square B. Square A looks dark grey. Square B looks white (in a shadow). The Reality: They are exactly the same shade of grey. (If you don't believe us, cover the middle of the image with your finger).

Why does your brain lie to you? Because it is "subtracting" the shadow. It knows that in the real world, a white square in a shadow should look darker, so it mentally "brightens" it to tell you the truth about the object's local color.

The Application: Why "Messy" Photos Are Fine When a judge looks at a student's work photographed on a shaky mobile phone in a dim classroom:

- The Eye receives "blurry, yellow-tinted" data.

- The Brain applies Perceptual Constancy. It subtracts the yellow tint (Color Constancy). It stabilizes the edges (Shape Constancy).

- The Judgement lands on the work itself.

Your judges are not rating the photography. They are acting as sophisticated Signal-to-Noise filters. As long as the work is legible, the human brain will "fix" the image quality issues automatically, ensuring the student gets the grade they deserve, not the grade the lighting dictates.

The "Equity" Twist: Why "Messy" is Actually Fairer

Here is the counter-intuitive truth: High-quality photos often introduce bias.

When we demand "perfect" portfolios - scanned at 600dpi, cropped perfectly, colour-balanced - we are unintentionally rewarding students who have resources. We are rewarding the student with the expensive DSLR camera, the latest iPhone, or the parent who knows Photoshop.

We call this the Production Value Bias.

By moving to "on-the-fly" mobile capture, you level the playing field. When everyone's work is captured quickly on a mobile device in the classroom, you strip away the polish. You force the judges to look past the presentation layer and assess the artifact itself.

It is the difference between judging a singer on an auto-tuned, studio-mastered track versus a raw acoustic set. The raw set is "lower quality" audio, but it is a much higher quality test of true talent.

The Evidence: The Clay Tile Experiment

We know this works because we have seen it in the data.

In a recent multi-school assessment with E-ACT, Art teachers were tasked with judging 3D clay sculptures. But they didn't have the physical sculptures; they only had simple 2D photographs.

If the "Perfect Photo" myth were true, reliability should have plummeted. Teachers should have been confused by the angles or lighting.

Instead, the reliability was incredibly high.

Why? Because the Art teachers used their Tacit Knowledge of materials. When they saw a highlight on the clay in the photo, their brains didn't just see a white spot; they inferred the wetness and texture of the surface. They used Perceptual Constancy to "feel" the weight and depth of the object through the screen.

They didn't grade the photography skills. They graded the art.

The Solution: Permission to Snap

This is why we are redesigning RM Compare to be Mobile-First.

We are building an interface that encourages "capture in the moment." We want to give you permission to stop stressing over scanners and start snapping.

- Don't waste hours setting up studio lights.

- Do take three photos from different angles (to give the brain more 3D context).

- Do trust your judges.

As long as the work is visible, the human brain will do the heavy lifting. It will filter out the noise, fix the lighting, and find the truth.

In Part 3, we will look at the final piece of the puzzle: How we can use this human superpower to build a safety net for AI.