- Data Sovereignty

Dark Patterns in AI Assessment: When “Consent” Steals Your Sovereignty

In earlier posts we argued that sovereignty is the only sustainable path for professional judgment, and that organisations need infrastructure which lets them own and operate their own intelligence.

There’s another layer to this: even if the architecture is centralised, the interface can quietly decide who wins. The way AI is presented in a product can make the difference between a conscious choice and a gentle shove.

That’s where dark patterns come in.

What dark patterns look like in AI tools

Dark patterns are design tricks that technically give you a choice, but practically steer you toward the outcome the vendor wants.

In AI assessment tools, they often appear at the exact moment you are asked to “turn on AI”.

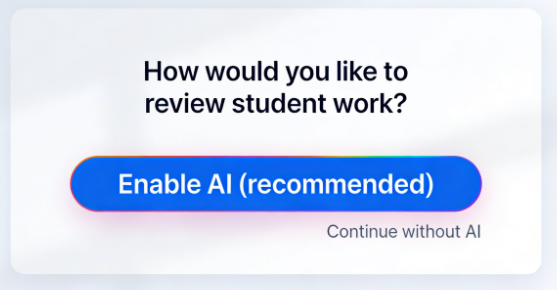

In this kind of screen, you can “Continue without AI”, but the interface clearly wants you to hit the big, glowing Enable AI (recommended) button. Size, colour, placement and wording all push in one direction.

👉 How to use: Select your role and setting above. The generator will use the title of this page to build your custom prompt.

Pattern 1: Asymmetric choices

A classic dark pattern is simple: make the preferred option huge and attractive, and make the safer option small and ignorable.

- The AI path gets a large, colourful button in the centre of the screen.

- The human‑only path is reduced to a low‑contrast text link tucked away at the edge.

- Under time pressure, most users will click the big button, often without fully reading what they’re agreeing to.

This isn’t neutral design. It’s using default bias and attention bias to drive adoption of AI, even when staff or data‑protection leads might have reservations.

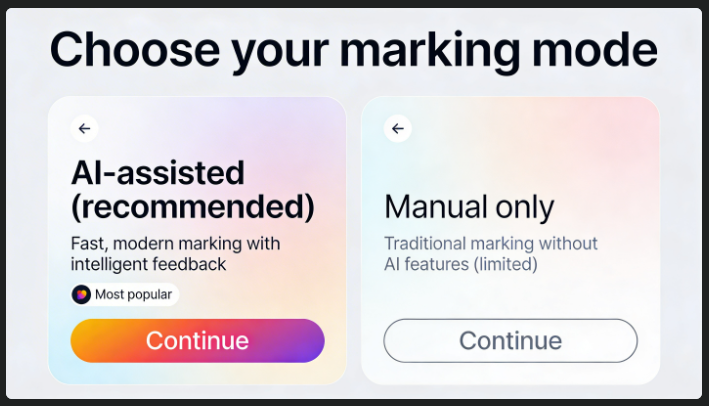

Pattern 2: Framing AI as “normal” and humans as “limited”

Language is another powerful lever. You can make one option feel modern and professional, and the other feel like opting out of progress.

In this style of choice:

- “AI‑assisted (recommended)” is described as fast, modern, and comes with a “Most popular” badge.

- “Manual only” is labelled as “traditional” and explicitly marked as “limited”.

Both paths exist, but only one is framed as something a competent, up‑to‑date professional would choose. The other is framed as second‑class.

This is more than marketing. It shapes internal culture: if AI is “recommended” and “most popular”, then questioning it can feel like being difficult, not diligent.

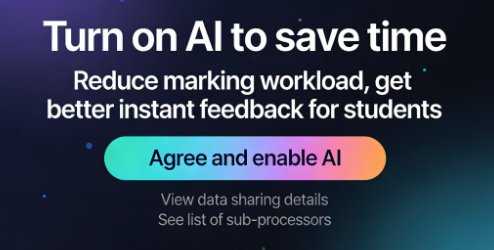

Pattern 3: Hiding the real trade‑offs

The third pattern is softer but just as important: make the benefits easy to see, and the risks hard to find.

Here the screen shouts about reduced workload and better feedback. The button to Agree and enable AI is big and central. Meanwhile:

- Details about what data is sent where are pushed into small “data sharing” or “sub‑processors” links.

- Understanding the implications takes multiple clicks and a lot of reading; saying yes takes one click and no effort.

When sovereignty‑critical information is separated from the decision itself, consent becomes a formality rather than a real choice.

Why these patterns are a sovereignty problem

Dark patterns are not just UX annoyances; they have structural consequences.

- They undermine meaningful consent. If most users are nudged into AI because it’s easier, prettier, or labelled “recommended”, it’s hard to argue that the organisation has made a conscious decision about where its judgment data flows.

- They normalise data harvesting. Every time AI is turned on by default in a wrapper model, new streams of high‑value scripts, recordings and judgments flow into someone else’s stack. Over time, that builds models, benchmarks and research outputs that live with the vendor, not with you.

- They obscure long‑term risk. The friction sits on the side of understanding: legal terms, data flows, sub‑processors, jurisdictions. The convenience sits on the side of enabling AI.

From a sovereignty perspective, the question is not just “is this compliant right now?” but “what kind of dependency are we quietly building for the next decade?”

A simple anti–dark pattern checklist

When you evaluate AI‑enabled assessment tools, you don’t need to accept these patterns as inevitable. You can ask for better defaults.

Look for consent flows that:

- Give equal prominence to AI on and AI off. Human‑only paths should be just as visible, with no shaming labels like “limited” or “not recommended”.

- Explain data flows on the same screen. At the moment of decision, you should see plain‑language answers to: what data goes where, for what purpose, under which jurisdiction, and for how long.

- Offer granular controls. You should be able to enable or disable AI per project or cohort, and ideally for specific groups of learners, without losing access to the platform.

- Allow reversal and exit. You should be able to turn AI off later and still export all your raw and derived data into your own systems.

- Avoid hidden reuse. Any reuse of work for research, benchmarking, or training should be explicit, genuinely optional, and easy to say no to.

If a product struggles with these basics, it’s worth asking whether its business model depends more on doing work for you or on harvesting value from you.

How we think about this in RM Compare

In RM Compare we’ve taken a strict line: our job is to convert professional judgment into high‑quality, machine‑ready data that lives in your ecosystem, under your control.

That has consequences for how we design:

- AI is not treated as the default or the “only serious” mode; it’s something you choose to bring into your own workflows.

- Choice screens must present human‑only and AI‑assisted paths with equal dignity and clarity.

- We assume you may want to run your own agents, in your own cloud, against your own judgment data—and we treat that as a success, not a threat.

The benchmark we use internally is simple:

Could you walk away, take your data with you, and still build your own AI on top of it?

If the answer is yes, then your sovereignty is intact. If the answer is no, the product (ours or anyone else’s) is just another wrapper with a glossy consent flow.

In an agentic world, your judgments are fuel. Dark patterns decide whose engine they power.